Maternal Health Disparities: An Intersection of Race and Rurality

October 2022

by Per Ostmo, MPA and Jessica Rosencrans, BBA

Funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), under the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Rural Health Research Gateway disseminates work of the FORHP-funded Rural Health Research Centers (RHRCs) to diverse audiences. This resource provides a summary of recent research, conducted by the RHRCs, on maternal health disparities.

Loss of Hospital-based Obstetric Services

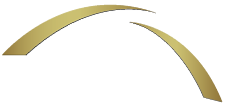

In 2014, a total of 2.4 million reproductive age women lived in counties with no in-hospital obstetric services.1 From 2014 to 2018, 53 rural counties (2.7% of all rural counties) lost hospital-based obstetric services, in addition to the 1,045 counties (52.9% of all rural counties) that never had those services during the study period.2 Loss of services were most frequent in rural noncore counties (3.5% of all rural noncore counties), where the proportion that did not have these services was already high (68.7% of all rural noncore counties).2 Figure 1 accounts for adjacency to urban counties and illustrates that loss of hospital-based obstetric services increased with rurality.2

Figure 1. Percent of Counties Which Lost Hospital-Based Obstetric Services by County Type, 2014-20182

Urban Versus Rural Hospitals

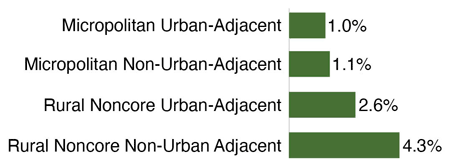

As of 2018, there were 1,883 urban hospitals and 987 rural hospitals providing obstetric services.3 Between 2010 and 2018, 154 rural hospitals had stopped providing obstetric services.3 The urban hospitals providing obstetric services had a median of almost 51,000 annual inpatient visits and 1,250 births, with 6.9% of these hospitals located in counties with a majority of residents who were non-White or Hispanic.3 The rural hospitals providing obstetric services had a median of almost 8,000 annual inpatient visits and 280 births, with 7.0% of these hospitals located in counties with a majority of residents who were non-White or Hispanic; 40.7% were located in noncore rural counties.3

The rural hospitals that stopped providing obstetric services had a median of almost 4,000 inpatient visits with 120 births, with 7.1% of these hospitals located in counties with a majority of residents who were non-White or Hispanic; 62.3% were located in noncore rural counties.3 See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Median Annual Births at Hospitals Providing Obstetric Services by Rurality, 2010-20183

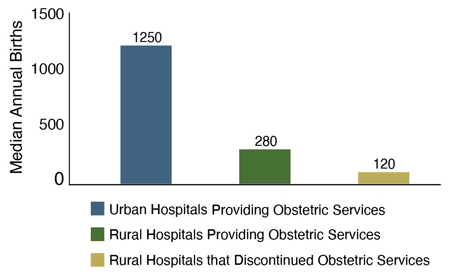

Obstetric Workforce in Rural Areas

The supply of obstetricians, advanced practice midwives, and midwives decreases with increasing rurality, and family physicians are more likely to deliver babies the more rural the location.4

The proportion of family physicians performing any deliveries dropped from 17.0% in 2003 to 10.1% in 2009, while the proportion of family physicians delivering more than 50 babies annually dropped from 2.3% in 2003 to 1.1% in 2016.4

In 2019, approximately 58.7% of rural counties had no obstetricians, 81.7% had no advanced practice midwives, and 56.9% had no family physicians who delivered babies.4 Furthermore, 30.8% of rural counties had no obstetric clinicians of any type.4 See Figure 3. These scarcities are likely even higher in non-core rural counties.4

Figure 3. Percent of Rural Counties Without Obstetric Clinicians, 20194

Racial Inequities in 93 Rural U.S. Counties

A 2022 study examined racial inequities in 93 rural U.S. counties with hospital-based obstetric care.5 In rural majority-Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) counties, life expectancy was 2.3 years shorter and median household income was more than $9,000 less than in majority-White rural counties.5

Compared to majority-White counties, in majority-BIPOC counties, more infants were born low birthweight (8.6% versus 7.7%), and more children lived in poverty (31.7% versus 18.3%) and in single-parent households (42.7% versus 29.0%).5 Services that were less available in majority-BIPOC counties than majority-White counties included local prenatal care (82.1% versus 100%), nurse home visiting for prenatal care (21.4% versus 46.8%), and perinatal mental health services (50.0% versus 72.6%).5

All 93 rural counties were found to have limited access to evidence-based family-centered models of care, but the deficiency was more pronounced in majority-BIPOC counties.5 Compared to majority-White counties, majority-BIPOC counties had reduced access to doula care (32.1% versus 58.1%), postpartum peer support groups (32.1% versus 56.5%), supportive groups for breastfeeding (71.4% versus 83.9%), and childbirth education classes (78.6% versus 95.2%).5

Access to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children – commonly known as "WIC" – was ubiquitous in both majority-BIPOC (100%) and majority-White counties (96.8%) with hospital-based obstetric care.5

Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

Severe maternal morbidity refers to potentially life-threatening complications or the need to undergo a lifesaving procedure during or immediately following childbirth.6 From 2007 to 2015, overall incidence of severe maternal morbidity and mortality increased from 109 to 152 per 10,000 childbirth hospitalizations.6 Average severe maternal morbidity and mortality was identified in 140 per 10,000 childbirth hospitalizations among rural residents and 135 per 10,000 childbirth hospitalizations among urban residents.6

Compared to urban residents who gave birth, higher proportions of rural residents who gave birth were non-Hispanic White (60.8% versus 43.6%), had Medicaid as their primary insurance payer (49.5% versus 42.8%), and lived in ZIP codes in the bottom national income quartile (48.6% versus 24.2%).6 When the size of the rural population was accounted for, an excess of about 4,378 cases of severe maternal morbidity and mortality among rural residents was revealed, representing residents who would not have experienced severe morbidity or mortality if they lived in urban areas.6

Non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, and Asian residents of both rural and urban areas had at least 33% increased odds of severe maternal morbidity and mortality compared to non-Hispanic White residents.6 Medicaid beneficiaries and patients who had no insurance at delivery had at least 30% increased odds, compared to those with private insurance.6

Preterm Births

Preterm birth is defined as babies born before 37 completed weeks of gestation and is the leading cause of death in children under the age of five years, globally.7 A study using 2012-2018 data from all U.S. counties examined singleton births; births of only one child during a single delivery.8

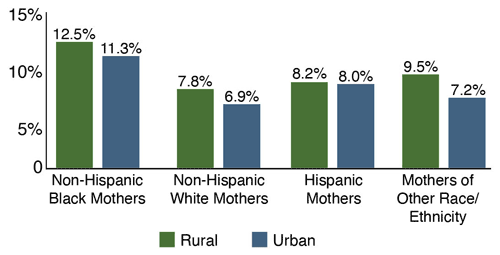

For all racial and ethnic groups, rates of preterm birth were higher for rural residents than urban residents.8 Non-Hispanic Black mothers had the highest rate of preterm birth, especially if they were rural residents (12.5% rural versus 11.3% urban).8 Non-Hispanic White mothers living in urban counties had the lowest rates of preterm birth (7.8% rural versus 6.9% urban).8 Hispanic mothers had the smallest rural-urban differences in preterm birth rates (8.2% rural versus 8.0% urban).8 See Figure 4.

Figure 4. Percent of Rural Counties Without Obstetric Clinicians, 20194

Medicaid Expansion in 2018

Medicaid programs fund approximately half the births in the nation.9 Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act has improved overall hospital finances and led to reductions in hospital closures in both rural and urban areas.9 However, Medicaid pays for obstetric services at significantly lower rates than private insurers, and many rural hospitals have large proportions of Medicaid patients.9

There is substantial regional and state-level variability in the number of rural hospitals that offer obstetric services to patients who may need them.9 Of nine states with highly racially diverse rural reproductive age populations (where >30% of rural women age 15-49 are BIPOC), seven had less than the median density of rural hospital-based obstetric services available (9 hospitals per 100,000 rural reproductive age women).9 Of the 11 states in the lowest quartile of rural hospital-based obstetric service density (3-7 hospitals per 100,000 rural reproductive age women), only three had expanded Medicaid, and one additional state had passed Medicaid expansion by 2018.9 This left seven states with the lowest density of obstetric service availability located in non-Medicaid expansion states.9

Conclusion

Fewer than half of all rural counties in the U.S. had hospital-based obstetric care services in 2014; and from 2014 to 2018, the most remote rural counties (noncore non-urban-adjacent) experienced the greatest reduction in obstetric service availability.1,2 The capacity of the obstetric workforce diminishes as rurality increases, with nearly 31% of rural counties lacking an obstetric clinician of any type in 2019.4 Furthermore, majority-BIPOC counties tend to have worse maternal and infant health outcomes and less access to maternity care services than majority-White counties.5 Finally, many states with the least access to maternal health care services, the highest maternal morbidity and mortality rates, and the most racially diverse populations are located in the South.9 Many of these states have not passed Medicaid expansion.9

Resources

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2017). Access to Obstetric Services in Rural Counties Still Declining, With 9 Percent Losing Services, 2004-14.

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2020). Changes in Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in Rural US Counties, 2014-2018.

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2021). Rural and Urban Hospital Characteristics by Obstetric Service Provision Status, 2010-2018.

- WWAMI Rural Health Research Center (2020). The Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of the Obstetrical Care Workforce in the U.S.

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2022). Racial Inequities in the Availability of Evidence-Based Supports for Maternal and Infant Health in 93 Rural US Counties With Hospital-Based Obstetric Care.

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2019). Rural-Urban Differences in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the U.S., 2007-15.

- World Health Organization (Accessed June 2022). Preterm Birth landing page.

- Southwest Rural Health Research Center (2021). Trends in Singleton Preterm Births by Rural Status in the U.S., 2012-2018

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2021). State and Regional Differences in Access to Hospital-Based Obstetric Services for Rural Residents, 2018