Post-Acute Care in Rural Areas: The Role of Swing Beds and Nursing Homes

March 2024

by Per Ostmo, MPA

Funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), within the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Rural Health Research Gateway disseminates work of the FORHP-funded Rural Health Research Centers (RHRCs) to diverse audiences. This resource provides a summary of recent research, conducted by the RHRCs, on post-acute care, swing beds, and nursing homes.

Post-Acute Care: Rural vs. Urban Areas

Patients who have received acute care services, but are not ready to safely return home, may transition to post-acute care (PAC). The PAC phase acts as a bridge between the hospital and the next steps to recovery. Types of PAC services include skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), home health, hospice, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and, unique to rural areas, swing beds.1

In 2014, 92% (1,817) of all rural counties had at least one facility providing post-acute SNF-level care, in the form of swing bed programs or SNFs.2 Counties with population densities less than 10 people per square mile were significantly less likely to have post-acute SNF-level care.2 Approximately 5% (101) of rural counties had only swing beds, 36% (715) had only SNF beds, and 8% (153) had neither swing beds nor SNF beds.2

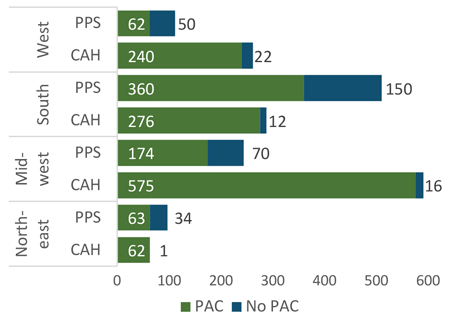

In 2015, 96% of Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and 68% of rural Prospective Payment System (PPS) hospitals offered PAC, but the percentage of rural hospitals offering PAC varied by region, by hospital type, and by proximity to SNF competitors.3 See Figure 1. Facilities that offered PAC were more often located in remote areas (those with a Frontier and Remote Area code) and in areas with fewer SNF beds.3

Figure 1. Number of Rural Hospitals Providing PAC by Census Region, 20153

A study using the 2012 National Inpatient Sample examined discharges to PAC (defined as skilled nursing care and home health) and found that rural patients discharged from a rural hospital were more likely to receive SNF or swing bed care and less likely to receive home health care than urban patients discharged from an urban hospital.4 However, rural patients received similar amounts of admissions to PAC overall when compared to urban patients.4

An analysis of Medicare Provider and Analysis Review Files and Master Beneficiary Summary Files from January 2013 through March 2014 examined rural providers’ market share of inpatient PAC services (defined as skilled nursing care and rehabilitation) provided to rural Medicare beneficiaries, resulting in three key findings.5 First, 90% of rural Medicare PAC discharges were for SNF-level care and 10% were for rehabilitative care.5 Of the SNF-level care provided to rural Medicare beneficiaries, 83% was provided by rural facilities, whereas only 35% of rehabilitative care was provided by rural rehabilitation facilities.5 Second, on average, rural beneficiaries had longer stays in rural SNFs than in rural swing beds (36.4 days vs 10.2 days).5 Third, while discharge from a rural acute hospital was almost always followed by discharge from a rural PAC facility, discharge of a rural patient from an urban acute hospital was only followed by discharge from a rural PAC facility about half of the time.5 Importantly, changes in market share could influence changes in access to PAC services as rural providers adapt to meet demand.5

What Is a Swing Bed?

A swing bed is a change in reimbursement status which allows certain small, rural hospitals to use their beds for either acute care or PAC.6,7 A patient “swings” from receiving acute inpatient care services and reimbursement to receiving SNF-level services and reimbursement while often remaining in the same hospital or even the same physical bed.6,7 While swing bed patients receive SNF-level care, they are not SNF patients. For example, swing bed patients in a CAH are patients of the CAH. Swing beds are intended to serve as a transitional phase of care that allows the patient to recover so they can be safely discharged—typically to return home or to a nursing facility.6,7

To be eligible for swing bed care, Medicare rules require that a beneficiary must have a qualifying 3-day inpatient stay in a qualified hospital or CAH prior to admission to a swing bed.6,7 The 3-day qualifying stay does not need to be in the same hospital as the swing bed admission.6,7 This allows patients who receive acute care far from home the flexibility to transition to a swing bed that is closer to their residence.

Prospective Payment System vs. Cost-Based Reimbursement

In 2015, almost all CAHs and around one-third of rural PPS hospitals reported Medicare revenue for swing bed services.1 In CAHs, Medicare pays for swing beds used for PAC using the same cost-based reimbursement as when the bed is used for acute care. In PPS hospitals, Medicare reimburses swing beds used for PAC the same as a SNF; when the bed is used for acute care, Medicare uses the PPS hospital formula.8 In total, Medicare PAC and hospice revenue as a percentage of net patient revenue was much higher for CAHs than for rural PPS hospitals.1

In an effort to reduce costs to Medicare, a transition from cost-based reimbursement to SNF PPS reimbursement for swing bed services in CAHs has previously been suggested.8 An analysis of this potential policy estimated the median change in CAHs’ 2016 operating margin to be -2.16 percentage points.8 The CAHs most impacted were smaller and more isolated, depended more heavily on swing beds, served a higher percentage of Medicare beneficiaries, were located farther from the nearest SNF, and were located in the South.8 The most financially fragile and most rural CAHs were most likely to be negatively impacted by the change.8

Nursing Homes

After post-acute care, some patients may require additional long-term care. Custodial care and skilled care are two types of long-term care.9 Skilled care refers to SNF-level or rehabilitation services ordered by a doctor and provided by licensed health professionals, like nurses and physical therapists, while custodial care refers to services ordinarily provided by personnel like nurses’ aides.9 Custodial care can take place at home or in a nursing home and involves help with activities of daily living, such as bathing or dressing. Medicaid may cover custodial care if provided in a nursing home setting.9 Medicare does not pay for custodial care or long-term services and supports.10

Not all nursing homes provide SNF-level services. Facilities that are dually certified by Medicare and Medicaid tend to provide both PAC and long-term care services.11 On the other hand, facilities certified only by Medicare tend to focus on PAC services whereas facilities certified only by Medicaid tend to focus on long-term care services.11

Interviews with rural discharge planners highlighted multiple challenges that nursing facilities face related to patients’ medical conditions.12 The most challenging medical conditions for nursing home placement included behavioral problems, complex care needs, dementia, and obesity.12 Additional barriers to finding nursing home placement included: shortage of staff with training and skills in behavioral health, dementia, and complex conditions; medication issues; lack of beds designated for geriatric care; scarcity of secured memory care units; and lack of bariatric equipment and physical barriers, such as narrow hallways and doors.12

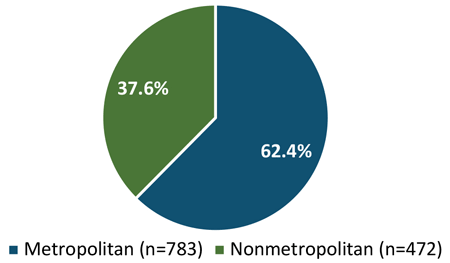

Nursing home closures present another challenge to patients receiving both PAC and long-term care. An analysis of nursing homes that included facilities dually certified by Medicare and Medicaid or facilities certified by only Medicaid found that between 2008 and 2018, 400 nonmetropolitan counties lost at least one nursing home and resulted in 40 new nonmetropolitan counties with no nursing homes (i.e., nursing home deserts).13 Of the 1,255 closures, 472 (37.6%) occurred in nonmetropolitan counties, accounting for about 10.4% of the facilities operating in nonmetropolitan counties in 2018.13 In contrast, 783 closures (62.4%) occurred in metropolitan counties, accounting for about 7.2% of nursing homes operating in metropolitan counties in 2018.13 See Figure 2. About 87.7% of the facilities that closed were dually certified by Medicare and Medicaid.13 Within nonmetropolitan counties, facilities that closed between 2008 and 2018 tended to be smaller in size, had lower total occupancy, had slightly higher Medicaid occupancy, and were more likely to be hospital affiliated compared to facilities that remained open in 2018.13

A nursing home closure in an isolated rural county will likely mean considerable travel distance and time to the next nearest facility. Although many states have emphasized home- and community-based services over institutional settings, the supply of home- and community-based services remains limited in rural areas.13 Furthermore, attempts to substitute in-home personal services are more challenging in rural areas given increased travel time to residential settings in rural areas.13

Figure 2. Proportion of Nursing Home Closures in Metropolitan vs. Nonmetropolitan Counties, 2008-201813

In 2019, 92% of all counties in the United States had nursing homes of any type (Medicare and/or Medicaid certified), but fewer noncore counties had nursing homes (87%) than metropolitan counties (96%) and micropolitan counties (95%).11 Nursing homes in noncore counties had fewer beds (78.6) and lower occupancy (75.1%) compared to metropolitan counties (beds: 117.4; occupancy: 80.1%) and micropolitan counties (beds: 96.7; occupancy: 76.4%).11 Compared to metropolitan counties, a higher proportion of residents in nursing homes in noncore counties had depression (41.1% vs. 34.5%), dementia or Alzheimer's disease (48.2% vs. 42.9%), psychiatric diagnosis (35.6% vs. 32.0%), and other mental/behavioral needs (25.0% vs. 19.8%).11 Nursing home residents in noncore counties were more likely to be female, older, and white than those in metropolitan counties.11 Among noncore counties without hospitals with swing beds, 25% had no Medicare and/or Medicaid certified nursing homes.11 The existence of hospital swing beds increased the availability of PAC services in noncore counties.11

Conclusion

The impact of swing beds can be felt by patients, CAHs, and communities. Swing bed patients are able to receive PAC close to home; can receive enhanced services not found in nursing facilities, such as infusions; and can benefit from continuity of care in the same bed with the same staff when remaining in the same facility that provided the acute care services.14 Swing beds benefit CAHs by allowing flexibility between acute and PAC care beds and stabilizing staffing schedules; by utilizing a reimbursement structure that promotes sustainability of acute care services; and by providing emergency preparedness flexibility, such as the ability to utilize beds during the COVID-19 surge.14 Finally, swing beds benefit communities by supporting the financial viability of rural hospitals, allowing these hospitals to remain open, and by bringing in additional services that also serve outpatient populations, such as physical and occupational therapy.14

After receiving acute care and PAC, placement in a nursing home may be necessary for additional long-term care. However, not all nursing homes provide SNF-level services, and nursing home closures in rural counties may result in nursing home residents being relocated to facilities farther from their home and social support networks. Furthermore, complex care needs and staffing shortages can make placement in a nursing home difficult.12 For individuals requiring SNF-level PAC, and not long-term custodial care, swing beds may provide the most appropriate care that is closest to home.

Resources

- North Carolina Rural Health Research and Policy Analysis Center (2017). The Financial Importance of Medicare Post-Acute and Hospice Care to Rural Hospitals.

- Southwest Rural Health Research Center (2020). Post-Acute Skilled Nursing Care Availability in Rural United States.

- North Carolina Rural Health Research and Policy Analysis Center (2018). Market Characteristics Associated With Rural Hospitals' Provision of Post-Acute Care.

- Burke, R.E., Jones, C.D., Coleman, E.A., Falvey, J.R., Stevens-Lapsley, J.E., and Ginde, A.A. Use of Postacute Care After Discharge in Urban and Rural Hospitals. The American Journal of Accountable Care. 2017;5(1):16-22.

- North Carolina Rural Health Research and Policy Analysis Center (2018). Rural and Urban Provider Market Share of Inpatient Post-Acute Care Services Provided to Rural Medicare Beneficiaries.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2020). State Operations Manual, Appendix W – Survey Protocol, Regulations, and Interpretive Guidelines for Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and Swing-Beds in CAHs.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2015). State Operations Manual, Appendix T – Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines for Swing Beds in Hospitals.

- North Carolina Rural Health Research and Policy Analysis Center (2020). Estimated Reduction in CAH Profitability From Loss of Cost-Based Reimbursement for Swing Beds.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2016). Custodial Care vs. Skilled Care.

- Medicare.gov (Accessed August 2023). Long-Term Care.

- RUPRI Rural Health Research Center (2022). Nursing Homes in Rural America: A Chartbook.

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2017). Medical Barriers to Nursing Home Care for Rural Residents.

- RUPRI Rural Health Research Center (2021). Trends in Nursing Home Closures in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties in the United States, 2008-2018.

- Rural Health Information Hub (2021). Understanding the Rural Swing Bed: More Than Just a Reimbursement Policy.