Rural-Urban Differences in Housing Crowdedness, Cost Burden, Stability, and Quality

November 2024

by Jessica Rosencrans, BBA, and Per Ostmo, MPA

Funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) within the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Rural Health Research Gateway disseminates work of the FORHP-funded Rural Health Research Centers (RHRCs). This resource provides a summary of recent research, conducted by the University of Minnesota RHRC, on housing as a social driver of health.

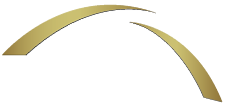

Crowded Housing

Crowded housing was defined as those reporting more than one person per bedroom in their household, except for couples needing only one bedroom. Overall, from 2015 to 2019, higher proportions of urban residents (18.8%) than rural residents (14.4%) lived in crowded housing.1 See Figure 1. While a higher proportion of rural residents (20.0%) than urban residents (14.3%) reported having any disability, adults without a disability were more likely to live in crowded housing, among both rural and urban populations.1 By race/ethnicity, overall, urban Hispanic adults had the highest proportion of people in crowded housing (40%), followed by both rural Hispanic and rural American Indian populations, which each had one-third of people in crowded housing.1

Figure 1. Prevalence of Crowded Housing by Rural-Urban Location, 2015-20191

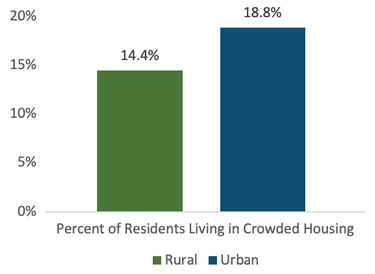

Housing Cost Burden

Housing cost burden was computed as the percentage of the household's monthly income that goes toward housing-related costs. Households were considered cost burdened when more than 30% of income was used on housing, or severe cost burdened when more than 50% of income was used on housing. From 2015 to 2019, higher proportions of urban residents reported housing cost burden (28.0%) or severe housing cost burden (12.6%) than their rural counterparts (21.0% and 9.2% respectively).1 See Figure 2. Over 35% of urban adults with disabilities and nearly 30% of rural adults with disabilities were housing cost burdened.1 Overall, urban "Other" race adults (those who do not identify as Hispanic/Latino, White, Black, Asian American/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or as multiple races/ethnicities) and urban Black adults had the highest proportions of people experiencing housing cost burden.1 Furthermore, 19% of both urban "Other" race adults and urban Black adults were severely burdened by housing costs, followed by rural Black adults (16.5%) and urban Hispanic adults (16.0%).1

Figure 2. Proportion of Residents Experiencing Housing Cost Burden by Rural-Urban Location, 2015-20191

A separate analysis found that from 2017 to 2021, proportions of households reporting housing cost burden increased to 32.7% for urban adults and 25.0% for rural adults.2 Importantly, this more recent analysis partially overlaps with the economic volatility of the COVID-19 pandemic. By geography, the Western Census region had the highest rates of housing cost burden for both rural (28.9%) and urban locations (37.0%).2 Additionally, California, Hawaii, and Massachusetts had particularly high rates of housing cost burden among both rural and urban households, ranging from 34.1% to 41.4%.2

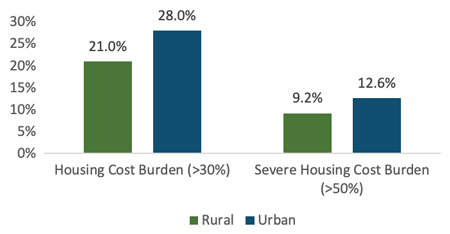

Housing Stability

In 2021, rural residents were more likely to own their homes than urban residents (76.4% vs 68.6%).3 See Figure 3. However, among renters, rural residents were nearly five percentage points more likely than urban residents to receive rental assistance (13.1% vs 8.2%).3 The likelihood of receiving rental assistance increased with age, and was higher for females, people identifying as non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and other/multiple races, as well as people who were divorced, separated, widowed, or never married.3 Conversely, receiving rental assistance was less likely for those with higher education, who were employed, and who were in better health.3 The likelihood of receiving rental assistance was also lower in the North Central/Midwest, South, and West Census regions, compared to the Northeast region.3

Figure 3. Proportion of Residents Who Own Their Homes by Rural-Urban Location, 20213

Additionally, in 2021, rural residents were found to be more likely than urban residents to have lived in their homes for more than 20 years (26.9% vs 19.9%) and less likely to have lived in their homes for less than one year (10.0% vs 12.0%).4 Among adults who have lived in their home for more than 20 years, rural residents were more likely to have a disability (16.6% vs 12.6%) and/or be in fair/poor self-rated health (24.1% vs 16.7%) than urban residents.4

Housing Quality and Adequacy

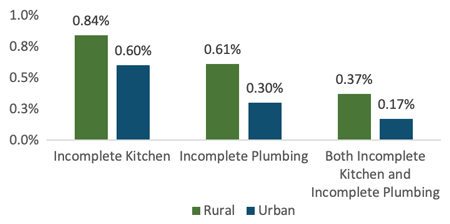

Housing quality was examined using two indicators. First, having incomplete plumbing was defined as missing either or both of the following: hot and cold running water, and a bathtub or shower, which must be located within the housing unit. Second, having incomplete kitchen facilities was defined as missing one or more of the following: a stove or range, a refrigerator, and a sink with a faucet – all must be located within the housing unit and portable cooking equipment did not qualify. Overall, from 2015 to 2019, higher proportions of rural residents (0.84% or over 284,000 residents) than urban residents (0.60% or over 1,265,000 residents) lived in housing with an incomplete kitchen.5 Rural residents (0.61% or over 207,000 residents) also had a higher proportion of adults living in housing with incomplete plumbing compared to urban residents (0.30% or over 636,000 residents).5 Furthermore, rural adults (0.37% or almost 124,000 residents) had higher proportions with both incomplete kitchen facilities and incomplete plumbing compared their urban counterparts (0.17% or over 357,000 residents).5 See Figure 4. Higher proportions of people with a disability had an incomplete kitchen or incomplete plumbing, compared to people without a disability, regardless of location.5 Among all racial/ethnic groups, rural American Indian or Alaska Native adults had the highest proportion of people with an incomplete kitchen (3.53%), followed by Asian American or Pacific Islander, urban American Indian or Alaska Native, and rural "Other" race adults (all less than 1.46%).5 Rural American Indian or Alaska Native adults also had the largest proportion of adults with incomplete plumbing facilities in their homes, regardless of rurality (5.13% or 33,000 residents).5

Figure 4. Percentage of Residents Living With Housing Inadequacies by Rurality, 2015-2019 5

Housing adequacy included conditions related to plumbing, heating, electricity, exposed wiring, and maintenance issues such as leaks, holes or cracks in ceilings, walls, and floors, and pests. In 2019, rural areas, urban clusters, and urban areas had similar proportions of housing units classified as severely inadequate (1.1% vs 1.1% vs 1.2%).6 Similarly, 4.3% of rural housing units were considered moderately inadequate, compared to 4.0% in urban clusters and 3.4% in urban areas.6 Although all three areas had similar statistics, rural residents had the lowest rate of living in adequate housing (94.6% vs 94.9% vs 95.4%).6 Rural housing units had higher rates of heating problems, utility interruptions, missing roofing or external building materials, and broken windows, while urban housing units had higher rates of flush toilet breakdowns, electric wiring problems, and indoor water leakage.6 Mice and rats in the home were more common in rural housing units than urban clusters and urbanized areas (21.2% vs 11.8% vs 9.3%).6 However, cockroach infestations had the highest prevalence in housing units located in urbanized areas (12.5%) followed by urban clusters (11.6%) and rural areas (6.8%).6

References

- Swendener, A., Rydberg, K., Tuttle, M., Yam, H., & Henning-Smith, C. Crowded Housing and Housing Cost Burden by Disability, Race, Ethnicity, and Rural-Urban Location, University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, 2023.

- Swendener, A., Schroeder, J., & Henning-Smith, C. Rural-Urban Differences in Housing Cost Burden Across the U.S., University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, 2024.

- Henning-Smith, C., Swendener, A., Rydberg, K., Lahr, M., & Yam, H. Rural/Urban Differences in Receipt of Governmental Rental Assistance: Relationship to Health and Disability, The Journal of Rural Health, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 394-400, 2023.

- Henning-Smith, C., Tuttle, M., Swendener, A., Lahr, M., & Yam, H. Differences in Residential Stability by Rural/Urban Location and Socio-Demographic Characteristics, University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, 2023.

- Swendener, A., Pick, M., Lahr, M., Yam, H., & Henning-Smith, C. Housing Quality by Disability, Race, Ethnicity, and Rural-Urban Location: Findings From the American Community Survey, University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, 2023.

- Yam, H., Swendener, A., Tuttle, M., Pick, M., & Henning-Smith, C. Rural/Urban Differences in Housing Quality and Adequacy: Findings From the American Housing Survey, 2019, University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, 2024.