Healthcare Access and Status Among Rural Children

August 2019

by Shawnda Schroeder, PhD

Funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), under the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Rural Health Research Gateway strives to disseminate the work of the FORHP-funded Rural Health Research Centers (RHRCs) to diverse audiences. The RHRCs are committed to providing timely, quality research on the most pressing rural health issues. This resource provides a summary of recent research.

Provider Access

Lower provider availability can make it more difficult for individuals to access care. A shortage of healthcare professionals is called a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA). In rural HPSA counties there is an average of 1,845 patients per physician, compared to urban non-HPSA counties (976 patients per physician). Rural counties also struggle with access to specialty providers. More than half (56.6%) of all rural counties in the U.S. do not have a pediatrician, which can have a negative effect on the health status of rural children.1

Health Status

According to 2010-2012 data, rural children ages 5-17:

- Had a higher disability rate (6.3%) compared to urban children (5%).1

- Were at a greater risk for unintentional injury and suicide compared to urban children, which can lead to permanent disability.1

- Reported significantly higher obesity rates compared to urban children. More than 33% of children in large and small rural areas were overweight or obese compared to 30.1% in urban areas. This is true after controlling for factors such as diet and exercise.1

- Were at a lower risk of death due to homicide compared to urban children.1

- Had a higher adjusted all-cause mortality rate compared to urban children.1

Rural teens 15-19 years old report a significantly greater teen birth rate (43.3 per 1,000) compared to urban teens (32.7 per 1,000).1 The rate of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) is also higher among the rural population. However, many of these infants are born in or transferred to an urban hospital due to greater need of specialized care that may not be available at a rural hospital. Continuing care for NAS infants once they are home is also a challenge in a rural setting where there are limited resources.2

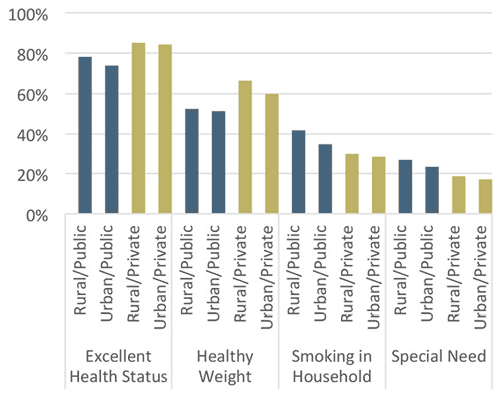

Beyond rural and urban disparities in health status, children who are on public insurance generally have more health challenges compared to those privately insured. See Figure 1. When compared to privately insured children, those on public insurance are significantly (p < 0.05):3

- Less likely to be in good health

- Less likely to be at a healthy weight

- More likely to have special healthcare needs

Figure 1. Children's Health Status by Geography and Insurance Type, 2011-20123

Health Outcomes

Although health status explores the current condition of rural children, health outcomes refer to the positive or negative effect of an intervention on a child's health. One commonly reviewed outcome measure is hospitalization or Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSCs). These are conditions such as asthma or diabetes that with regular ambulatory care (regular check-ups and monitoring) can be easily managed.4

Rurality is not solely associated with an increased likelihood of hospitalization from ACSCs among children. However, ACSC hospitalization was greater among racial/ethnic minority children and those with Medicaid or self-pay as an anticipated source of payment.5

Oral Health

Similar to overall health status and health outcomes, rural, minority, and publicly insured children experience greater disparities in oral healthcare access and oral health status than their peers. The percentage of pediatric dental visits increased from 71.8% in 2003 to 77.2% in 2012. However, rural children still lag behind urban children in the rate of preventative dental visits and overall dental health.6

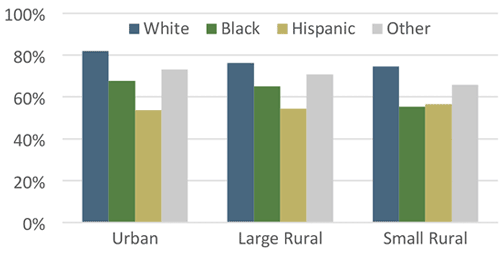

In both rural and urban areas, minority children report poorer oral health than white children. See Figure 2. As an example, 74.6% of non-Hispanic white children in small rural areas reported their teeth to be in excellent or very good condition compared to only 56.5% of Hispanic children.6

Figure 2. Proportion of Children With Reported Excellent or Very Good Condition of Teeth, 2011- 20126

Rural counties often lack an adequate number of dentists, with 22 per 100,000 residents compared to urban counties with 30 per 100,000. Rural children also often lack dental coverage.1 In addition, 42% of dentists in rural counties are 56 years of age or older compared to only 38% of urban dentists, putting rural counties at risk of losing a larger number of dentists to retirement. Lack of dental coverage and provider availability makes it less likely that children will receive regular check-ups and cleanings.1

Tobacco

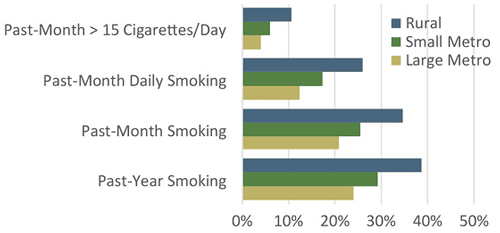

Tobacco use impacts both overall health and oral health status. Data from the 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey has shown that rural teens have a higher rate of both tobacco (36.1%) and alcohol (41.2%) use compared to their urban counterparts (26.5% and 30.4% respectively).1 Rural children (15.3%) are also more likely than urban (8.7%) to have a smoker in their family household exposing them to secondhand smoke.1,3 Rural mothers are more likely to smoke, smoke often, and smoke heavily compared to their urban counterparts.7 See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Maternal Smoking Behavior by Rurality7

Conclusion

There are many areas in which rural children face significant health status disparities compared to urban children. These include healthcare provider access, obesity rates, tobacco use/exposure, and oral health status. However, these disparities can be reduced with focused consideration in various areas. More information on this topic can be located in the Recap Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage Among Rural Children.

Resources

- Rural and Minority Health Research Center (2016). Current State of Child Health in Rural America: How Context Shapes Children's Health.

- University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (2018). Opioid-Affected Births to Rural Residents.

- Maine Rural Health Research Center (2017). The Role of Public Versus Private Health Insurance in Ensuring Healthcare Access & Affordability for Low-Income Rural Children.

- Rural and Minority Health Research Center (2015). The Intersection of Residence and Area Deprivation.

- Rural and Minority Health Research Center (2015). Rural Area Deprivation and Hospitalizations Among Children for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions.

- Rural and Minority Health Research Center (2017). Trends in Rural Children's Oral Health and Access to Care.

- Maine Rural Health Research Center (2015). Implications of Rural Residence and Single Mother Status for Maternal Smoking Behaviors.